Working families across California are getting pushed further away from opportunity — from cities and job centers with schools, health care facilities and amenities. Nowhere is this more evident than where I live, Los Angeles, the nation’s second-largest metro area and one of the wealthiest regions in the world.

Thousands of Angelenos are stuck with costly, exhausting commutes because they can’t afford to live near their jobs, burning through more than $14,000 a year on transportation — much of it on car payments, gas and maintenance. This isn’t an accident. For decades, our cities have systematically banned apartments and condos, preventing working people from living near jobs and transit systems their taxes fund.

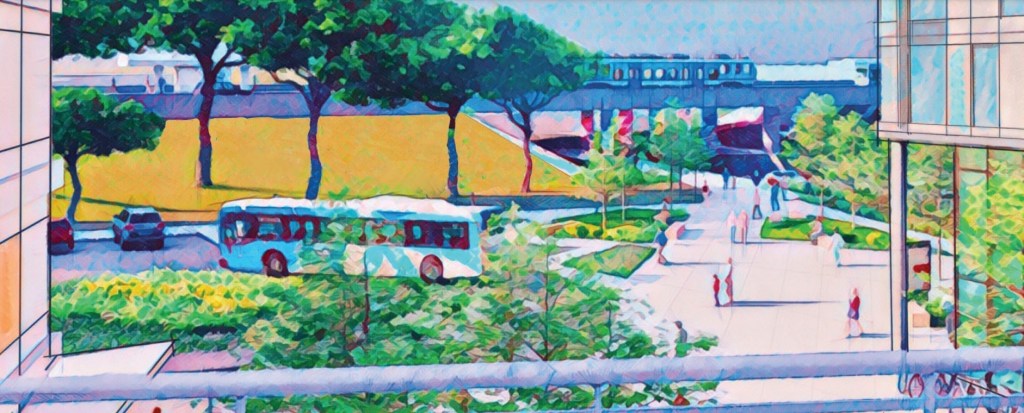

The solution is simple: reform land use and housing policies to allow more homes near transit.

I’ve spent my career helping people find homes — not just for the right square footage, but for homes that allow them to connect the rest of their lives. As a real estate sales manager, I’ve supported agents through over 1,000 home sales and seen the same struggle play out: families who want to live close to their jobs, childcare or aging parents — and can’t.

In L.A. County, families earning the median income of $88,000 can’t afford sky-high rent, much less a median home price approaching $1 million. They move farther out, sacrificing time, money and quality of life to keep a roof over their heads.

Meanwhile, taxpayers have spent billions expanding our transit network, adding stations in places like South Pasadena, Redondo Beach and East Long Beach. Yet red tape blocks housing near these stops, making it nearly impossible for working families to live near the infrastructure they’ve already paid for.

A bill in the state legislature, SB 79, offers a commonsense fix: requiring cities to allow more housing near transit — up to seven stories near subways and mid-rises near less frequent Metrolink stops. Projects that meet these standards would be streamlined for approval.

This approach puts money back in peoples’ pockets. Families not reliant on cars save thousands yearly, which is often the difference between barely getting by and putting money towards their dreams — a college education for their kids, a retirement plan or even a GED or vocational certificate to change their career path.

My nieces are a clear example of what’s at stake. My 19-year-old niece would wake at 3 a.m. to walk to the bus stop, transferring across four buses to make it to her 7 a.m. class at Rio Hondo College in Whittier, often on little sleep. Her younger sister, working toward her degree at Cal State Long Beach, was balancing a part time job to afford $50-$60 each way on rideshares because of the lack of reliable transit near home.

We don’t always call this displacement, but that’s what it is. They weren’t just priced out of housing — they were nearly priced out of access to education, work and opportunity.

More homes near transit reduces the risk of displacement. California’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office found that Bay Area neighborhoods adding the most housing experienced half the displacement rates of areas that blocked development.

It’s also critical for climate action. Cars and trucks account for 30% of the state’s climate pollution, a figure that remains stubbornly high because so many Californians are forced to drive long distances. Research shows people who live near reliable transit or in walkable neighborhoods, drive half as much as those in car-dependent areas, reducing traffic, commute times and air pollution.

I’m old enough to remember when teachers lived near schools and nurses near hospitals. That didn’t change because of their preferences — it changed because we banned the housing they could afford.

We’ve let perfect become the enemy of good, and working families pay the price. SB 79 is a step toward fairness: it lets people live near the infrastructure we’ve already built, and ensures good housing doesn’t die in endless meetings.

Monica Rivera serves as chair of the Gateway Cities chapter of Abundant Housing LA. She wrote this column for CalMatters.

<