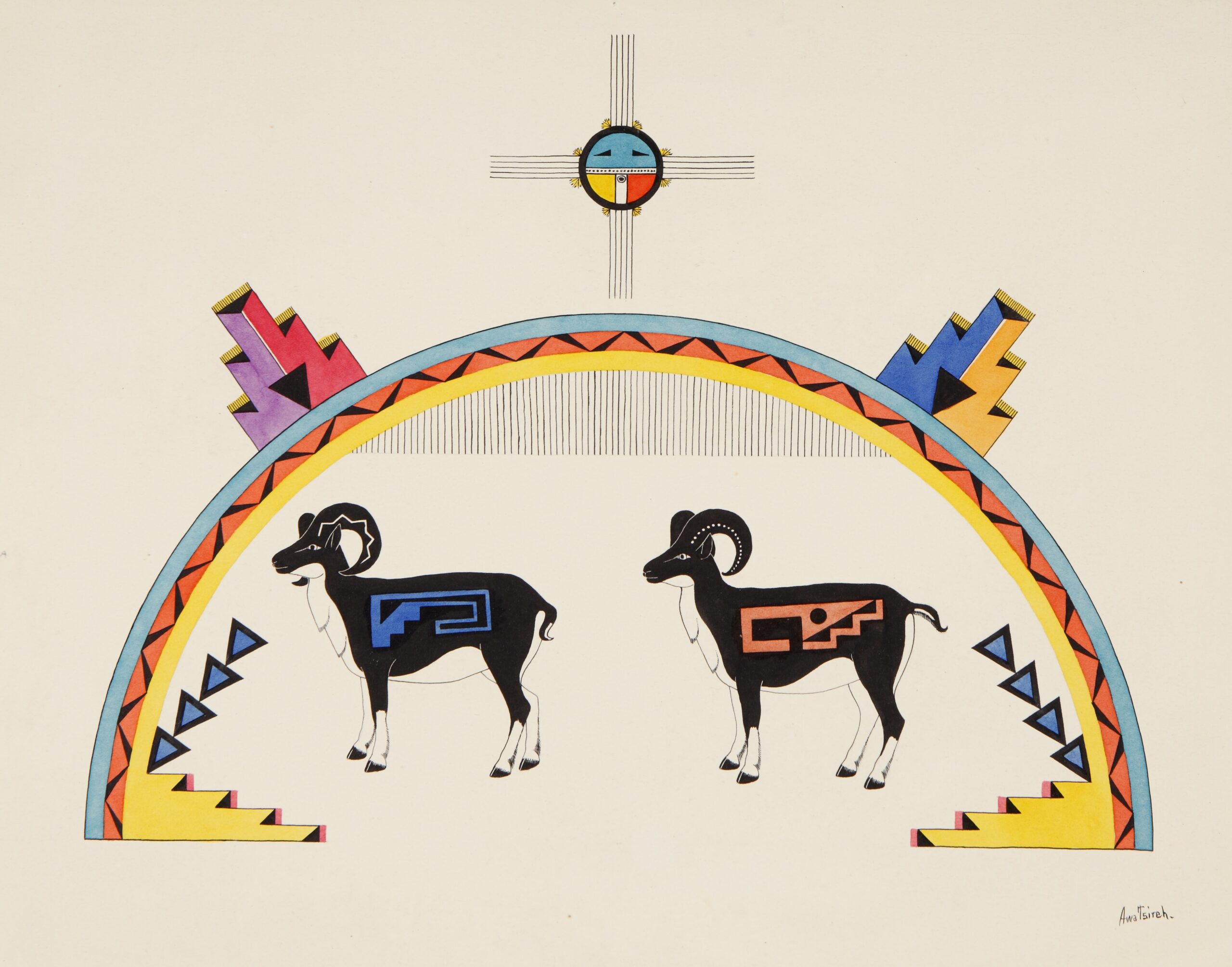

Among the many standout ontemporary and historical artworks on display in the 12th iteration of SITE SANTA FE’s biennial international exhibition, Indigenous Tewa artist Awa Tsireh’s Untitled (Bighorn Sheep and Rainbow), ca. 1928-30, radiates impressions of half-familiar, half-uncanny figurative shapes with especially compelling and deceptively simple-seeming clarity. Corralled by an overarching rainbow in three vivid colors that ties the composition together, and painted in a “flat” style that many Native Southwestern artists became known for early in the 20th Century, stand two bighorn sheep, depicted primarily in black and white, lined up neatly one behind the other. Each is marked on the side with striking geometric symbols—one in blue and the other in a pale carmine orange.

These mysterious patterns are among multiple signs that much more might be going on below the surface, for example, with what might be revealed through specific, symbolically representative codes. In this instance, in keeping with Tewa cosmology, those codes could reference the deeply embedded metaphysical connections that living forms possess, beyond the physical, while implicating it. Even further below the surface are also layers of not immediately apparent history that led to the production of such striking cultural expressions. In the case of Tsireh (also known as Cat Tail Bird and Alfonso Roybal), these included his cross-cultural interaction with a large number of non-Indigenous artists, teachers, collectors, curators and patrons, as well as with his many other artistic family members, alongside developing relationships he had with masked or coded cultural information forged within a secret society within the larger Tewa community of which he was a member.

New Mexico abounds with distinctive flora, fauna, geological formations, waterways, climactic conditions and manifestations of human nature—as well as intimations of what is beyond the natural—that is, the supernatural. Once Within a Time—the current SITE SANTA FE International—is that rare art biennial which, while drawing on a wide field of hundreds of international creative participants, manages to also procreatively inhabit and reflect some sensibilities that are highly specific to a region.

In a show of this scale, pursuing any singular, coherent concept is elusive. Though storytelling is one thematic declared by the exhibition’s curator, Cecilia Alemani, rather than pursuing any linear narrative, the biennial’s installation and layout in multiple locations around Santa Fe propose spiraling paths of possibility for viewers to contemplate and enter into via related constellations of imaginative approaches to different thematic considerations. Alemani is also curator of New York City’s High Line contemporary art programming, as well as of the widely celebrated 2022 Venice Biennale. Some of the emphasis on creative representations by globally Indigenous artists and a strong surrealist cast that gave mood to Alemani’s Venice exhibition (titled The Milk of Dreams, borrowed from the novel of the same name by Surrealist artist Leonora Carrington) also manifests in the SITE SANTA FE show.

Some earlier surrealist-tinged work also pops up in Once Within a Time. Several fine, darkly luminous landscapes in oil on canvas from the mid-20th century by Agnes Pelton, for example, are shown with curvilinear whorls or vortices suggestive of the supernatural superimposed. What runs glowingly throughout the larger exhibition is a kind of grounded magical realism generated from within the cultural and physical ambience of New Mexico. (Even the German-born Pelton’s offerings reflect viewpoints from an adoptive daughter to the greater U.S. Southwest desert region.)

Once Within a Time takes its title from a recent, semi-animated film by venerable director and long-time Santa Fe resident Godfrey Reggio, whose own thematic intent is capacious in striving to represent the complex and sometimes questionable relationships that humans have developed with both nature and technology. Borrowing Reggio’s title for the even more expansive art exhibition—the largest and widest in scope coming out of SITE SANTA FE to date—newly commissioned creative projects mingle alongside other recent contemporary artworks, interspersed with vintage creative work and other cultural ephemera from prior generations. Visiting in person exposes viewers to well-gathered distillations of research-based art and curation, world-making moving images and immersive and atmospheric experiences, in addition to the physical and retinal pleasures of sculpture and painting.

Beyond the storytelling thematic, other themes that manifest include Indigenous lifeways and perspectives, concerns stemming from larger political histories and cross-cultural conflicts, and particular outgrowths of technology. There is also a small riot of very varied human figures featured among the erotics (and tribulations) of human bodies. Overarching all these categories that might be more or less useful to think with is an implicit thematic of how global and local art production circulates and intermingles, and how different understandings might occur with each new recontextualization.

Among the sets of artwork concerned with the human body and individual representations and social understandings of it, a group of paintings by British author D.H. Lawrence occupies a large position. Lawrence, a visiting habitué of New Mexico, is more known for his writing, which controversially revealed and explored sexual relationships usually left more hidden, but he was similarly concerned with erotic interests in his paintings. The works in the exhibition were officially deemed “obscene” in Britain and still remain censored there. Explicitly responding to Lawrence’s turbulent and writhing human figures in updated compositional style, contemporary Swiss painter Louise Bonnet is featured at SITE SANTA FE with some engorgedly decadent and pneumatic human forms that cavort and contort in cropped and fragmented glimpses in seeming extremis.

In some sense, the largest component of the biennial, distributed through more than a dozen sites in and around Santa Fe, encourages visitors to attend to the uncertain relationships any of us might have with unknown other bodies. In entering the show at SITE SANTA FE itself, viewers must pass by the handful of diminutive, youthful, lifelike figures of French-Austrian artist Gisele Vienne’s 3 Dolls (2003-24), whose uncanny realism works both when they are encountered on their own in their large, otherwise nearly empty room as well as when they are surrounded by and become part of the visiting multitude of living human figures.

There are some challenges to the layout and installation of the exhibition. In a second gallery beyond 3 Dolls is the vastly smaller scale of work by Tewa artist Helen Cordero (an engaging set of diminutive ceramic figures) and Kiowa artist N. Scott Momaday (whose totem-shield etchings from the 1970s are enlivened with handwritten elegies to warrior life on the Plains). These works require closer attention to notice and comprehend, positioned as they are away from the larger reach of the gallery, which is dominated by a sweeping landscape mural by Argentinian painter Dominique Knowles and U.S. artist Simone Leigh’s larger-than-life, much-exhibited sculptural pieces that powerfully blur lines between the human figure and built structures. Partially built and adorned in raffia and oversized cowrie shell-shaped components, Leigh’s two untitled works reference African cultural elements still generative in the diaspora. The work of Momaday hangs on a nearby wall, somewhat occluded by the more massive pieces, Cordero’s figures dwarfed and tucked away in a corner behind glass.

Though international in scope, the show is not intended as a comprehensive survey or snapshot of global contemporary art production, nor of the state of the globe. There is plenty from Europe and East Asia, but from Africa, Latin America and West Asia, not so much. There are only a few references to specific, significant, large-scale contemporary conflicts or pointed political issues such as war, mass migration or climate change, though there are several pointers to the impacts of nuclear power. New Mexico, of course, has been key in the development and use of radioactive materials that continue to affect the landscape, lifeways and health of generations of humans and other living creatures.

Such tracking of political interventions on human lives manifests here in at least three notable instances:

- Mexican-American artist Daisy Quezada Ureña’s thoughtful installation Past [between] Present (2025) at the Palace of the Governors of archivally sourced historical objects and empathetic porcelain replicas of clothing from individuals along the U.S.-Mexican border that track the impacts of regional colonial history and oppression.

- David Horvitz’s elegantly embodied installation flock of wingless birds (2025), consisting of 4,553 large glass marbles—one for each Japanese-American prisoner detained in the World War II concentration camps nearby. The marbles were fired with bits of soil from the camps and are spread across the floor of a light, airy space just up the road from the site of incarceration.

- Joanna Keane Lopez’s striking Batter my heart, three person’d God (2024) features a wall constructed of regional material and techniques of adobe, with an upended bed mounted on it—a dislocation that calls out the odd juxtaposition of real domestic lives with early U.S. nuclear development that was conducted inside such locally designed buildings.

Among the more intriguing, far-flung and diverse sites through which the larger exhibition offers the dynamic of a scavenger hunt is a group of work featured at Finquita, the rustic site of a former foundry in the Tesuque village outskirts of Santa Fe. An extraordinary, evanescent ambience is created in one room there with Uzbeki artist Saodat Ismailova’s As We Fade (2024). The installation conjures an unusually numinous space via a video projected through twenty-four fabric rectangles suspended down the length of a large, dark, open room. The set of projected film clips highlights women’s roles in maintaining cultural traditions in Central Asia. The slow billowing of the thin sheets serving as translucent projection screens as visitors wander through the dim and unfinished former metalworks creates shifting glows, waxing and waning with varying clarity and lucidity for each projected image’s quality. In a sense, light itself is one of the physical materials of the piece. Meanwhile, the fluttering of images paradoxically helps make more alive and alluring the near-century-old archival footage that’s projected along with more recently captured moving images of obscure rituals on the sacred “Throne of Sulaiman” mountain in Kyrgyzstan. A sort of down-gearing of temporality is part of its effects: the unstill images, along with the unstill surfaces they are projected onto, complexify and call attention to the illusion generated by moving images more generally. There is a sense that the animating force underlying these movements is spiritual as much as physical.

Some other sly and softening takes on technology include Navajo artist Marilou Schutz’s yarn-woven circuit boards and Peruvian artist Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s recreation in Protomorphisms: AGC Rope Driver Module (2022) of the Apollo Guidance Computer from the 1960s in her coded-seeming hanging tapestry of copper and fiber, loose-woven like the pre-conquest Indigenous South American Inkan quipu, which recorded not only the raw data of agricultural enterprise and tax information but also the social relations caught up with them. In a different vein of scientistic elaboration, Karla Knight’s enticing multi-coded work channeling speculation on extraterrestrial visitation to Earth (and particularly based in the New Mexican desert) in half-familiar modes from popular culture is startlingly apt in the New Mexico Military Museum.

As other avatars of Santa Fe Indigenous culture who coalesce the storytelling theme of the larger exhibition, Pablita Velarde and Helen Cordero are both, like Tsireh, long-past participants in cross-cultural interactions with non-Indigenous teachers and patrons insistent on adapting as well as preserving traditional ways, and, for Velarde at least, targets of disapproval by tribal chiefs for recording stories that had hitherto been only orally transmitted. Storytelling, of course, is endemic to all human cultures, but the self-conscious coalescing of these artists’ approach to it—very much an interactive process with a developing art market encouraged by non-Indigenous collectors and patrons in and around late 20th-century Santa Fe—makes you realize they weren’t just selling things but adapting their way of life and art.

The specifics in the examples of Cordero’s work included in the show are illuminating: in all of her eight ceramic pieces, a large central figure (usually a seated human with closed eyes and wide open mouth—though there is also one friendly-looking turtle) is attended to or attached to by multiple smaller human figures. In the case of several of these, the smaller bodies number over a dozen. These dynamic characteristics for most of these active-looking smaller bodies suggests an attendance to the larger storyteller figure that is directly physical and tactile as much as or more than the obviously auditory or visual—perhaps the way humans absorb most of their cultural “lessons,” while in the active pursuit of living life itself? In Cordero’s particular playing out of a storyteller motif for which she (and eventually scores more Indigenous artists from the Cochiti Pueblo region she lived and worked in) became known, the figures embody the cross-generational basis by which culture and social reproduction are transmitted.

Other, more contemporary efforts from Indigenous artists in Once Within a Time include the impressive array of abstract elements in Terran Last Gun’s series of drawings under the overarching title of Another Human Being Experience, done in ink and colored pencil on surfaces that update another, earlier cross-cultural influence: the 19th-century Indigenous artists’ appropriation of European American colonizers’ accounting ledgers. Last Gun’s update is accomplished through a “mix of cultural legacies,” including geometric abstraction that would not be out of place in Constructivist or other earlier 20th-century approaches to abstraction, but doing so while incorporating Blackfoot archaeological elements and visual motifs taken from Indigenous Pilkani traditions.

At the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, whose mandate has long been exhibiting contemporary Indigenous art, the small array of Navajo Emmi Whitehorse’s recent paintings merge the abstract and figurative with many finely sketched details of organic-seeming elements—plant fragments, topographical features, meteorological phenomena—most immersively in the large yellowish field of Cloud Gate (2025), in which the artist uses oil, pastel and chalk applied to paper on canvas to hint at a storm of rain floating in a numinous spatial field.

The inclusion of Indigenous cultural production amongst the products of a larger set of more global contemporary imaginations is, of course, not a singular manifestation of cross-cultural mingling—it’s also a reminder of the panoply of cultural possibilities of how humans might co-exist in the world. Awa Tsireh’s work was featured on the world stage, as it were, as far back as the 1932 Venice Biennale (though it would be generations before another Indigenous American Choctaw/Cherokee artist, Jeffrey Gibson, was featured in 2024 in the American Pavilion of that particularly prominent global cultural venue). But in an era of continuing homogenization and especially narrowing of what is officially acknowledged and supported as “American art,” it is a compelling reminder to be able to access afresh and recurringly the most multi-dimensional matrix possible of creative Indigenous production.

Returning to the idea of not only figuratively but literally discovering what might lie hidden underground, Taiwanese artist Zhang Xu Zhan’s stunning multimedia installation in a subterranean gallery at the Santa Fe International Museum of Folk Art embodies themes of life and mortality and transformations that occur between or overlapping those two states. The installation’s centerpiece, Compound Eyes of Tropical (2024), is a tour de force, 16-minute, stop-motion animation in which dancing, hunting, boundary-crossing creatures cavort wildly, accompanied by a mesmerizing soundtrack influenced by Indonesian gamelan music. The intricacy and hints of something both magical and surprisingly realistic communicated through the movements of the handcrafted models of animals are preternatural, and the larger themes connect to the artist’s family history of both folkcraft and funerary matters. In addition to the enchanting and engrossing primary projected video, a second video plays separately on an upended flatscreen monitor, zooming in on a strange leaning tower of eight or nine long flies stacked atop one another—flies being another key figure of multiple perception and transformation in the centerpiece video.

The darkened basement room also contains a series of altar-like representations of related creatures from cultural folktales perched atop speakers and an assortment of crafted animal figures selected from the museum’s collection, ensconced in vitrines nearby. All the walls and the ceilings of the underground space are covered in layers of rolled-up local newspapers, simulating a thick, soft, skin-like layer for a cave or grotto effect, while sitting atop another medium-scale newspaper sculpture mound is a paper sculpture of a water buffalo whose ears contain words from its newsprint material (“powerful” and “Santa Fe”). A human being is just visible through a small piece of mesh covering the buffalo’s open mouth.

These striking figures hidden away below ground remind that—like the show itself, sprawling, redolent with hidden meaning and bridging the physical with the spiritual—there is much below the surface still to explore. What might usually be masked can resonate with important ideas and experiences in far-flung locales, including our relationships to life and death themselves, once they are revealed through creative evocation.

More in art fairs, biennials and triennials

<