The guidelines for prospective flight attendants in the 1950s sound more like an open call for models than standards for airline employees. In one 1955 document, TWA spells out their air hostess qualifications: “Age, 20-27; Height, 5’2” to 5’8”; Weight, 100 to 135 pounds scaled to height,” “must have clear skin,” “must be unmarried, although the company will accept widows or divorcees without children.”

These rigorous, and retro, requirements outlining the archetypal air hostess persisted into the 1990s when women brought a case against U.S. Air, now American Airlines, New York Historical curator Nina Nazionale told Observer. The case, which raised but didn’t eliminate weight restrictions for flight attendants, revolved around the airline’s policy that cabin employees maintain a “firm, trim silhouette, free of bulges, rolls or paunches . . . for an alert, efficient image.”

While flight attendants have always received some level of emergency training—first aid to start and then extensive training in safety and evacuation protocols—the job was largely viewed, discriminatorily, as “woman’s work.” Nazionale explained that in the 1930s, United Airlines hired actual nurses: the commercial craft of the era tended to be small and low-flying, in a constant, vertiginous dance of landing and taking off. Passengers often felt unwell and required care. But besides being caretakers, these attractive young women served as shiny distractions. In the 1960s, marketing materials like posters went so far as to ramp up the sexual allure of the ‘stews’—think ads with the words “Fly me” in bold beside photographs of flight attendants.

Yet despite these derogatory practices, stewardessing was a massive opportunity for young women from modest families who wanted to travel the world. At the front of “Dining in Transit,” now on at the New York Historical, sits a vitrine showcasing a classic TWA hostess hat. Nazionale mentioned that she met with the daughter of the owner of the chapeau; she said the position was the best thing that ever happened to her mother, even if she had to quit when she got married.

The exhibition, though it considers the plight of early flight attendants, is actually centered on the food they served—along with that eaten on other vessels in the early 20th Century. It’s a niche topic, but one that reveals much more than simply our eating habits. The materials here engage with social issues and global conflict. But foodies worry not: the culinary takes center stage, and many vintage menus full of mouth-watering options are on display.

“It was very brilliant,” Nazionale said, “because they took what is a need and made it a desire.” Dining experiences became marketing devices for airlines, trains and boats. She was particularly interested in spotlighting what she called the “extraordinary within the ordinary.” And so the show includes reams of historical and art-historical artifacts related to the theme—ornate menus, photographs of maximalist dining rooms and even a cookbook—in the small Pam & Scott Schafler Gallery. In one corner, a stylish blue television cycles through film clips from the 1930s through the 1950s that address the motif of eating on the move.

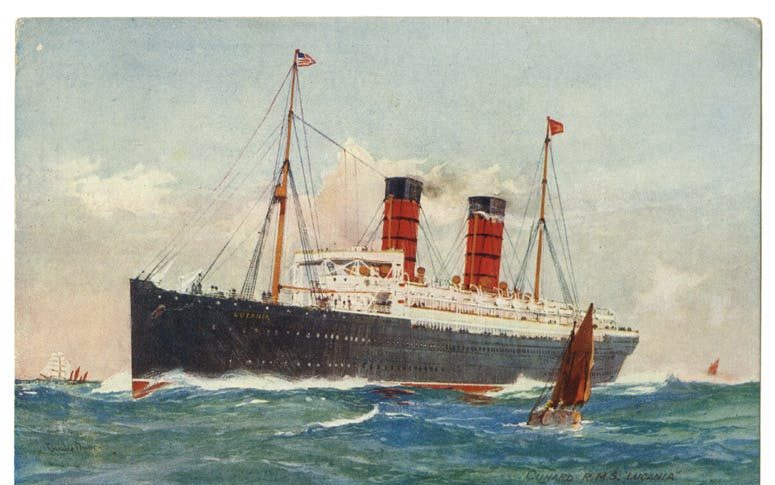

Many vessels and vehicles, in planning their fare, borrowed from the cuisines of Europeans—most notably the dining experience français, seen as the gold standard. A 1906 menu from “Ritz’s Carlton Restaurant” aboard the S.S. Kaiserin Auguste Victoria is complete with swirly lettering and curlicues. Celebrity Parisian chef Auguste Escoffier oversaw its kitchens and the creation of these highly choreographed meals. Menus on other modes of transport include such dishes as “cépes à la grecque,” “consommé froid en tasse” and “compôte of pears, damsons, blackberries and whipped cream.” That said, regional American cuisine also played a large part in honing the culinary identities of different vessels, especially with signature dishes and comfort foods.

For Nazionale, research is the best part of the curatorial process. One discovery leads to the next, and you’re soon immersed in a world of enlightening articles and distinctive objects. The majority of the materials in “Dining in Transit” come directly from New York Historical’s own repository—Nazionale’s impetus for the exhibition was their robust menu collection—but the exhibit borrows additional digital materials from sources like Duke’s David M. Rubenstein Library and the San Diego Air and Space Museum Archive; the only physical borrowed object is a 1911 “Good Things to Eat” cookbook self-published by Rufus Estes.

Estes was one of many formerly enslaved Black men hired by the Pullman Palace Car Company. “It was not a secret that Pullman wanted to hire formerly enslaved Black men,” Nazionale said. The label text reads that “He valued their service experience, specifically the behavior they learned while enslaved: deferential accommodation,” but it’s worth pointing out that Black workers unionized in 1925, which led to an improvement in pay and treatment. Nazionale explained that “Pullman families” transformed into a cultural tradition that brought communities together, and this history—and its subsequent ripple effects—is full of nuance and complications.

Other transportation companies hired chefs from all over the world. United Airlines brought in Swiss chefs to jazz up their offerings. A menu from the early 1950s portrays cartoon images of three chefs with puffy white hats and typed bios beside “The Hollywood” meal.

As Americans gravitated toward tourist destinations like Hawaii in the postwar years, airlines conjured holiday menus to make travelers feel like each journey was extra special. National and international conflict undoubtedly affected the ways these vehicles operated, not only altering routes but also changing menus because of rationing laws.

Visually, the exhibition offers a unique gustatory window into what traveling was like in the days before slimline seats and draconian baggage fees. But to get a literal taste of early twentieth-century transportation cuisine, make your way to New York Historical’s restaurant, Clara, which is currently serving desserts inspired by the delicacies featured in “Dining in Transit.”

“Dining in Transit” is at the New York Historical through October 26, 2025.

<