When photography was invented around 1850, it was quickly recognized not only as an art form but also as a scientific and ideological tool. In the immediacy of a photograph, there was not just a document of a moment but a potential to reveal deeper truths—about the world around us, about the way we see it, and about human beings themselves. At the same time, photography became the first medium to democratize art, making it possible for anyone to possess an image of themselves or their loved ones—where previously, a portrait had to be commissioned. It was from these historical reflections that our conversation with the young and sharp-eyed photographer Joseph Cochran II unfolded, when Observer met the artist at “Public Work,” currently on view at Swivel Gallery in New York.

Cochran treats photography as a tool of sociological study. Each picture becomes an epistemology of human existence, manifesting in its being and becoming as individuals interact within society. “For me, photography has always existed in this fascinating space between objective, scientific observation and subjective social commentary,” Cochran told Observer. “That tension is what makes it so powerful.”

Reflecting on how photography and film shaped modern perception and mirrored social structures, Frankfurt School critic Siegfried Kracauer once argued that photography doesn’t just document reality but also reveals structures and meanings otherwise invisible to the eye. The photographer, in Kracauer’s words, is “seeing into the life of things.” A photograph, beyond its surface realism, always holds metaphysical and social depth. By then, photography had already become a tool of sociology. “That type of photography was also drawing from fields like public relations, which emerged in the 1920s, and from efforts during the New Deal to document infrastructure,” Cochran explained. “It was a way to communicate with people, because we could no longer trust drawings or paintings—they were biased. The camera, on the other hand, was seen as impartial, capturing only what the observer saw.”

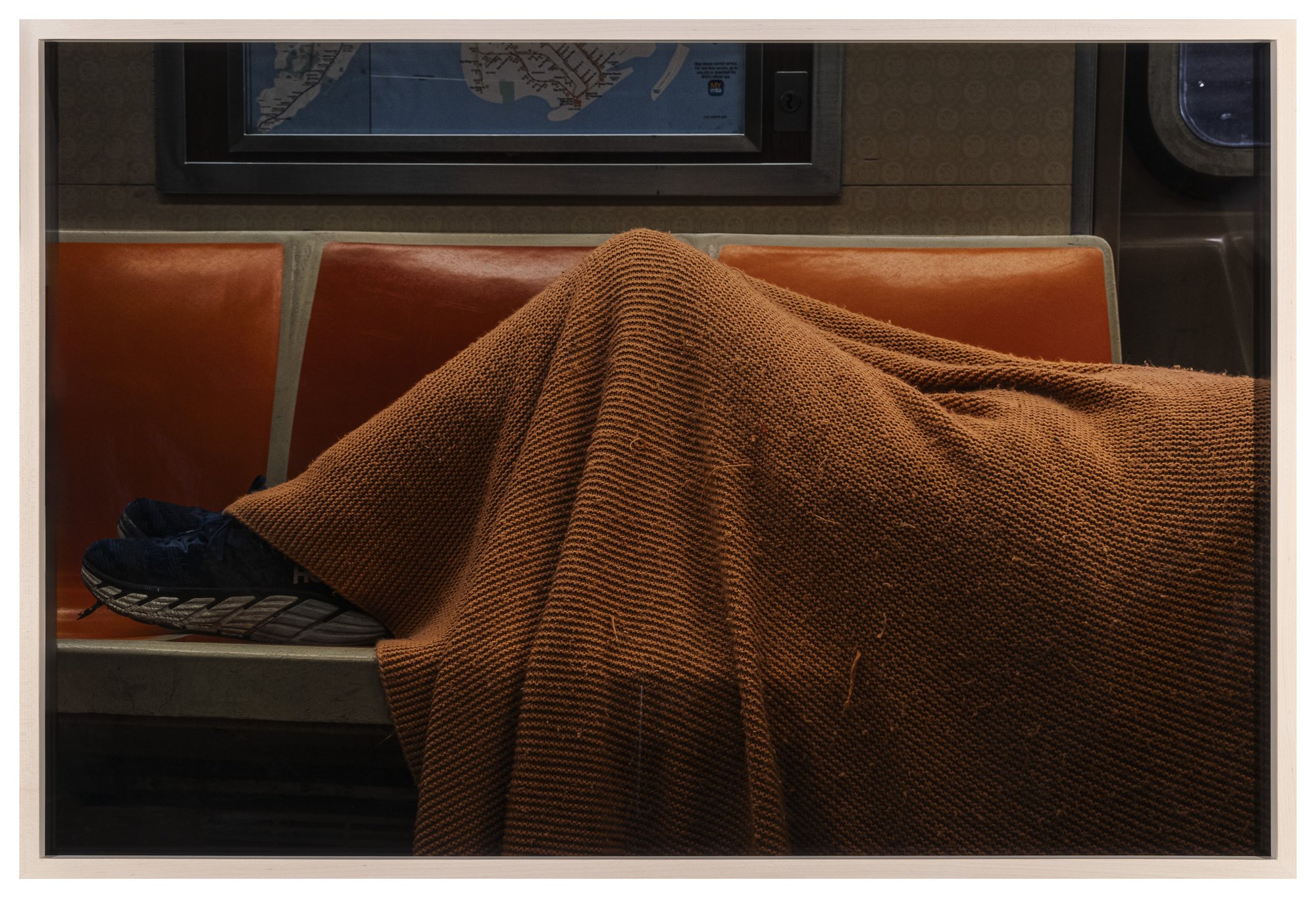

Following in the footsteps of photography masters like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gordon Parks and Dawoud Bey, Cochran II approaches the medium through a poststructuralist and anthropological lens, emphasizing the importance of the signified—the “phenomena” that emerge as image and symbol in a fleeting moment. For Cochran, photography is a way to capture these moments when society reveals itself through seemingly trivial, mundane gestures in shared spaces, on the street, during a conversation. His practice blends photography, sociology and radical empathy into a quietly profound form of civic meditation.

His images resonate with both the Ashcan School in painting and the American Realist tradition in documentary photography, each committed to rendering everyday life as it was lived. Like Lewis Hine, Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, Cochran uses the camera both as a record of urban and human life and as a tool for observation and understanding—before offering any critique. For him, photography is at once a social study and social work, an extension of his civic role as an educator deeply engaged with the city’s diverse communities. Photography becomes public work, attuned to the way society moves and breathes, captured in the microdynamics of individual interaction that reflect collective survival strategies. Cochran’s practice investigates how public life is structured, sustained and strained, and how photography, by paying attention to its subtlest cues, might intervene.

“Photography is both the newest and the purest tool we have to record humanity and the life we live, especially in contemporary times,” he reflected during our conversation. “Photography is the newest artistic practice, even if someone might bring up digital art. Photography as an art form is only about 170 years old. We still don’t fully understand its potential.”

Once his photographs are enlarged and installed in the gallery, it’s obvious that Cochran’s work is a direct attempt to bring viewers closer to the truth of contemporary America while intentionally leaving the frame open-ended. His approach resists didactic interpretation, encouraging instead a symbolic, metaphorical and poetic reading that makes room for empathy with the subject.

After all, the paradox of photography lies in the relationship between the sensorial immediacy of the image and object and their symbolic potential, and the final meaning always depends on aesthetic, cultural and ideological context. The medium’s apparent simplicity conceals its deep complexity, particularly its capacity to capture not beauty but those rare moments when things reveal themselves as they truly are, outside any pre-established narrative.

Consider photographs like Chinatown (2019) and Ghettowaser (2019), which are emblematic of the photographer’s role in postmodern and post-digital media culture. They are not merely depictions of urban life; they engage with iconography and painterly references, especially through their use of light and composition, while simultaneously allowing specific communities to speak for themselves. Each invites viewers to explore contemporary rituals and survival practices, attempting to construct meaning from the everyday.

Particularly resonant in its portrayal of today’s confusion and noise is Reality Show II (2021). The image captures the raw intensity of women screaming at each other, trying to be heard as they share their stories, as if caught inside an American reality show where only volume guarantees visibility. It’s a soap opera, a drama in motion, and simultaneously a mirror of contemporary human interaction, especially in the U.S., where people grapple to be heard and to understand their deeper selves within a constant societal performance. And yet, Cochran’s work moves beyond simply documenting the political—it seeks to study human behavior. The political and the economic are embedded, not as statements, but as the lived fabric of daily life, woven into the micro-politics of existence.

Cochran’s understanding of those dynamics is inseparable from his own lived experience. Growing up in Harlem, the son of two drug-addicted parents, he was immersed early in the chaos and hard clarity of New York City. He speaks little of that past, often dismissing it as a collection of distinctive moments—episodes of heightened, often forced, awareness that nonetheless shaped the perspective he brings to his work today.

“There was a brief period of my life where I did not know the future,” writes his gallerist Graham Wilson in Cochran’s most recent monograph. “I sat idly, in reference to both myself and the sedan I nearly lived in, on the corner of Mother Gaston and Sutter Avenue. Commotion ruled my surroundings—ambient sirens and flashing lights, people running from place to place, hustles crowding the sidewalks and a palpable sense of violence in the air. You could almost taste it. It was an unshakable atmosphere…. My acuteness at the time was at its peak, and there was something tangible in that. I performed my duties under a guise, glimpsing into lives I had no part of during my thirty seconds of cash and carry, then moved on. At that moment in my short years, I did not yet know Joseph Cochran II, but I knew his place and disposition. This was Brownsville, Brooklyn—home to Mike Tyson, the 69th safest precinct out of 69 in the city, and home to one of the most dynamic photographers of the 21st Century.”

At one point, Cochran was removed from his precarious family situation by the child welfare system and placed in a Brownsville project. “I was coming from a similar space in Harlem, but I had never lived in the projects before I came there,” Cochran recalled. At the time, Brownsville was the murder capital of America, and that’s where he found himself growing up—alone. “It was like one of the most dangerous places on earth,” he said, describing the project as more like a ghetto. He remembers telling the social workers it was an open-air prison, even without bars or cells. His clarity at such a young age was striking. “I came from classic tenement housing, an idyllic situation, to seeing how people who look like me, and other poor people, are really subjugated.”

That heightened awareness of his surroundings, which now informs his photographs, was born from the danger he experienced growing up. He learned to constantly assess his environment, to remain alert, to observe. At the same time, Cochran reflected, that awareness was nurtured by his grandmother’s peaceful guidance. “She taught me early how to look at the world, trying to understand my place, but also, most importantly, asking why something is the way it is. Asking why.”

<